March, 2005, pp 210-213

Ugo Rondinone, etc.

(translation)

For the November 28,

2004 "Arts and Leisure" section of the New York Times, Roberta

Smith offered her annual take on the art world. Entitled "Chelsea

Enters Its High Baroque Period," the critic eschews the numerous

and repeated complaints levied at that part of Manhattan's grid falling

between 14th and 29th Streets, west of 7th Avenue. Where some artists,

dealers, communities, and critics increasingly worry over what they see

as the onset of homogeneity, mediocrity, and commerce-even an insidious

return to conservatism- Smith opts to cast her oppositional, if not wholly

surprising, vote of confidence: "Chelsea is a delight," she

gushes, "a carnival without equal, the greatest showplace for contemporary

art on earth-and never more so than right now, as the gallery count rises

faster than ever."

Such a privileging

of rapid growth and multiplication (a section of Smith's piece is aptly

titled "Do the Math" and opines, "If one gallery is good,

two or three are even better) is not wholly unfounded. Better, one imagines,

to see people clamoring for art than turning their backs on it. And yet,

one wonders-taking Chelsea as simply one limit case-how a shift in understanding

that posits more as an indicator of quality affects not only gallery spaces

but the art being shown, to say nothing of its audiences. Indeed, one

has only to look at the kind of spaces that epitomize Chelsea (a majority

of them designed by a single architect-Richard Gluckman)-gutted, sterilized

warehouses that often "wow" much more than anything hanging

on the walls there.

If it sounds as though

I am about to launch down the by now familiar path of Chelsea-bashing,

don't despair. As Smith points out, Chelsea is hardly occupied by only

Gagosian-size gallery spaces, and even such behemoths occasionally show

wares that not only stand up to their sites but literally render them

irrelevant (a recent, if counterintuitive, example at Gagosian was a breathtaking

DeKooning show). In addition, all manner of small- to mid-size galleries-Metro

Pictures and Murray Guy among them-not only continue to open but, perhaps

more impressively, to persist (often having themselves tracked the western

migration from Soho or the East Village). Yet, the significant closing

of spaces like Pat Hearn and American Fine Arts in the last years is devastating

and impossible to quantify, particularly because these spaces far exceeded

their ostensible functions; worse, such endings hardly resonate for a

majority of gallery-goers who, while imagining they enter a community

by cocktailing at Lot 61, have no need for history since galleries seem

to magically multiply all around them.

All this to say that

Smith's use of "High Baroque" with regard to Chelsea is curious.

When I think the term, I'm happily recalled to Bernini, though I'm somewhat

sure this isn't what Smith had in mind. The word baroque is generally

used to connote effusive recourse to ornamentation and choreographed tension-whether

in the plastic arts, music, or architecture. And yet its etymology from

the 18th century (and arguably even earlier) links it to irregularity

in objects as unrelated-and as particular-as pearls, teeth, and warts.

Such idiosyncratic examples would seem to site the baroque, at least initially,

in the eccentricity of superficial details, whether of an individual or

an entire building. In addition, the "baroque" can be thought

as the theatrical staging of difference: and this not necessarily a pleasing

pose.

Smith's description of Chelsea as a carnival, then, would seem to coincide

neatly with her invocation of the Baroque, given that both can be seen

as celebrations of and by way of exaggeration. (It bears blatantly overdetermined

mentioning that the etymology of "carnival" is in fact nearly

identical to that of "carnivore.") But, my love of Bernini aside,

there are less benign, shallow, conceptions of the Baroque to be had.

Walter Benjamin, for instance, in his early work, The Origin of German

Tragic Drama, held the Baroque to be inextricably linked with a kind of

shortsighted, melancholic tethering to the world. Continued recourse to

extravagant physical details and settings meant that time itself came

to be conceptualized differently. Rather than retaining an abstract, and

therefore anticipatory relationship to historical time, people became

literally grounded, bound in a relationship to time that took on spatial

dimensions. Benjamin described this Baroque conceptualization of history-one

that bred passive melancholy rather than a will to act or produce-as resonant

with the later effects of capitalism.

It seems, then, at a moment where Chelsea seems to quite ceremoniously

perform a privileging of space over history, there is no arguing with

Smith's assessment, even while deeply disagreeing with her terms. Chelsea

has hit a Baroque moment (though I would argue "neo" rather

than "high"). Where the forces of community, politics, and art

history were visible everywhere in the art spaces of ten years ago, every

exhibition mounted these days feels sprung from a sparkling tabula rasa.

And so, it is, indeed, the space that we experience rather than any context

for it. (Benjamin wrote that in the Baroque "chronological movement

is grasped and analyzed in a spatial image.") To this end, one might

argue, most of the spaces we come to view art in (these getting grander

by the minute-museums like MoMA make Gagosian look piddly) can never really

be occupied so much as filled.

And, to get to the

review part of this essay, this is hardly the case only for audiences

who, weaving from doorway to doorway, make their way from one space to

another. Indeed, artists are called upon increasingly to make work that

itself has a more spatial than historical relationship to time. One particularly

Baroque (in this regard) recent exhibition was by the Swiss artist Ugo

Rondinone, his third solo show at the largest of Matthew Marks's Chelsea

spaces (out of a total of three.) I am a cautious fan of Rondinone's work

but this exhibition-one that approximated a pop-up fairy-tale book through

which I was ostensibly invited to wander-was a picture perfect rendition

of the Baroque I've outlined here.

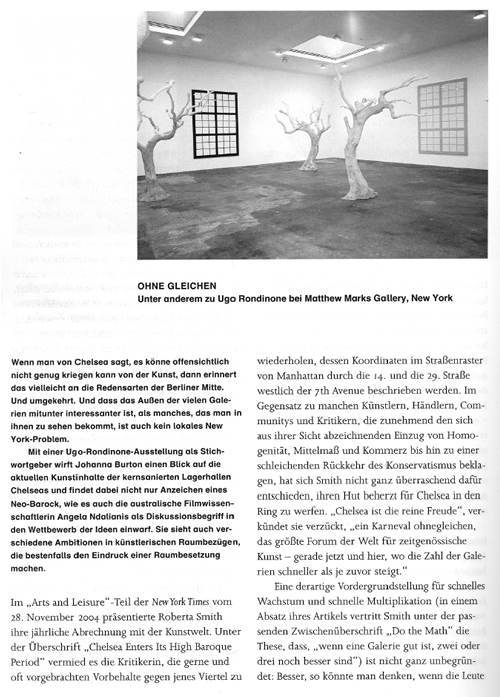

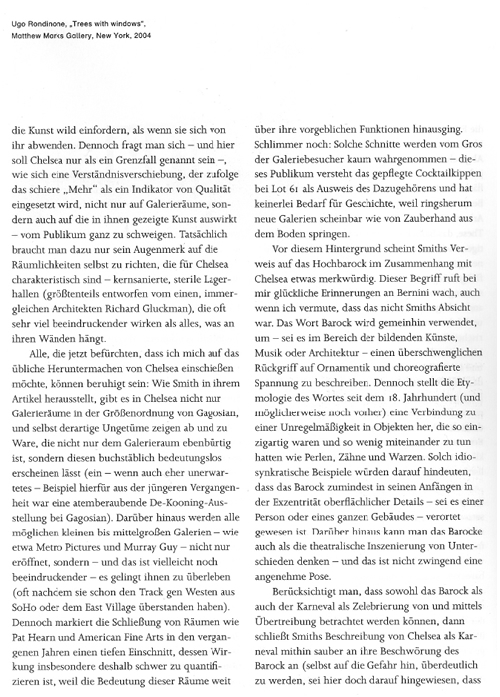

Comprising a rainstorm made of chain link, a post-and-lintel forest, a smattering of gigantic black-cast masks, resin trees, and three windows revealing only the walls, Rondinone's exhibition was titled Long Gone Sole. Though homophonic wordplay was clearly intended by the artist, it is uncanny the degree to which the phrase "Long gone soul" so better expresses how Rondinone's constructed space operated. Indeed, there was something whimsical and uncanny and even very sad about the installation, and yet this was a vulgar mix of emotions that seemed to force itself upon viewers rather than being produced by them. Walking through the gallery was to be surrounded: by a stage set, by so many willfully antipodal objects that at once announced a relationship to the past and yet rescinded it. The gallery was full of other people; we all walked around each other just as we did the resin trees.

A study in contrast: This week, I went to a performance at The Kitchen by Tracy + The Plastics. Carried out in an upstairs gallery whose painted black walls reminded me of my high school theatre, the piece was ostensibly musical in nature, but it self-consciously touted a communal element as well. Wynne Greenwood, who by way of a video screen plays all three members of her band, had teamed up with a sculptor, Fawn Krieger, to build a rather dumb looking carpeted bleacher that was meant to approximate a living room. About fifty people could squeeze onto this living room island, and from the moment we were all seated, we were made aware of our own normalized mute status as spectators, asked by various participants of the production to join in rather than sit back. As is almost always the case in such situations, this was both embarrassing and a failure. And yet, the performance-which began before and lasted after "Tracy" ever took the stage-was meant precisely to shore up some of the conditions of passive spectatorship.

More particularly, the installation, called ROOM, was conceived to "re-imagine the consciousness raising groups of the 1970s feminist movement and the potential revolutionary spaces of close bodies, living room histories and dialogue," as the accompanying brochure written by the artists puts it. I'm not fully convinced that this "re-imagining" of communal feminist spaces worked as such, but that doesn't mean it didn't work. For a change, and accompanied by a sensation that ranged from uncomfortable to ecstatic, I was in a room not filled but occupied.

-Johanna Burton