Interview

with Wynne Greenwood (Tracy + the Plastics) and Fawn Krieger

by Lanka Tattersalli

by Lanka Tattersalli

The following interview developed as an email discussion on the occasion of the premier of ROOM, a project by Wynne Greenwood in collaboration with Fawn Krieger, commissioned by The Kitchen. ROOM is an immersive video environment during the day that serves as a stage in the evening for performances by the feminist art punk band, Tracy + the Plastics. Playing the role of each band member, Greenwood performs live as Tracy, with Nikki and Cola present as video projections.

ROOM will be on view at The Kitchen from February 7 - 15, 2005. Tracy + the Plastics will perform in ROOM February 10 - 12, 2005 at 8pm (2/11 & 2/12 late night shows at 10pm as well).

Lanka Tattersall: First, I'd like to ask you a bit about the history leading up to this collaborative project. How did you meet? What drew you to each other's work? What were some of the ideas that you shared (or disagreed on) in developing the concept for ROOM?

Fawn Krieger: Wynne and I met at the Milton Avery graduate school for the arts Bard College.

At the beginning of school, she came to the door of my studio, and told me how much she loved my work. I remember feeling a sense of support, a kind of openness that was so powerful and inspiring. As I watched her work unfold as well, I felt these questions come up inside of me, mostly about freedom, the freedom to live and define oneself with so much liberty as well as conviction. When I see a woman take this role for herself I am so excited for her, but when I see her willing to inspire a consciousness for others to take this step, it feels angelic. What I learn from Wynne is a kind of fearlessness combined with saturated hope and openness. I believe in her vision because it assumes the intelligence, creativity, and engagement of her audience.

Composite digital drawing, Wynne Greenwood & Fawn Krieger

Before this project I had been working with themes of protection, survival, and security within structure-- particularly in domestic spaces. I think, in developing this project, I was interested in making space for others to recognize, grow, transform, and heal in. When Wynne asked me to collaborate with her, she expressed an interest to me in what it means to take up space- to use it, to own it with consciousness and integrity. We share a desire to support women, to establish a sense of belonging, strength and positive history with and for them, for us. We are both investigating a mythical and perhaps mystical kind of space where fantasy/play and reality/grittiness merge. I think also, in very different ways, we are both very invested in the space of the home and the moment of transformation. In ROOM, feminist consciousness brings these three spaces together- the space of the woman, the space of the home, and the space of change.

The challenges, for me, have been to really learn how to let someone into a very internal, creative space. I feel so safe and trusting with Wynne that this challenge has only yielded a stronger and deeper sense of safety and trust in her and within ROOM.

Wynne Greenwood: I was first totally into Fawn’s cool and un-doubting presentation of these unreal and really fantastical shaped and sized objects that she made. I just remember feeling like yeah, this woman's re-imagined world is no joke and neither is mine, although both of our work has the total capability of being humorous or cartoony or whatever. I remember specifically thinking I wanted her to make some giant mushrooms that I could sit on. From the beginning of my relationship with Fawn's work I've wondered what it would be like to inhabit it.

This last summer I was again inspired by Fawn's work, which I saw to be structures for this new utopia, where she was building out instead of up and really beginning to wonder what a non-hierarchical building would look like. When Sacha Yanow from The Kitchen suggested I collaborate on this residency with a sculptor I already knew who I wanted to work with.

I remember the first time we met to talk about ROOM at this diner near her house. Was I eating my eggs and potatoes in a weird way? Did I have hot chocolate foam left on my chin? As we talked about the shape of the project and asked new questions, important questions, my doubts left. And they haven't come back.

LT: Wynne, this is the first time that you have performed within a constructed immersive environment. Fawn this is the first time you’ve made a structure on this scale that incorporates video, performance and a live audience. What have some the challenges and pleasures of this been? How have you integrated your individual ideas together?

WG: This is also the first time I've made any video for an installation. The installation videos are different from the videos that will be performed with. It was really confusing to think about the installation because I'm so used to making videos that I stand with and goof around with. It's really physical for me. My Tracy + the Plastics videos occupy the space they're in immediately. They begin and then they end and there's a really specific way they're seen (which is so exciting that that specific space is being made more specific - and specifically open - with ROOM).

The installation is more about the building of the space. The physical space of the room, and the emotional space of Fawn and my collaboration.

I'm really right in the middle of making all the videos right now, and so this question is a little daunting to answer. But a couple days ago I was having such a hard time feeling connected to the tracy + the plastics video and I couldn't figure out why. I was using green screen to place nikki + cola in front of this wallpaper design I had made months ago. I thought for all these months it was this wallpaper design for sure. Then looking at it projected in ROOM it was so disconnected from everything else in the space. So I asked Fawn to make a background for the video. We had spent so much time planning and building the physical room we forgot to think about the projected room of the video.

Fawn asks me new questions about space and helps me find a language to answer them. The space of my videos is so flat. My interaction with the videos is so flat. I always felt a depth of a shifting of space that I couldn't totally get to. Fawn added a new perspective.

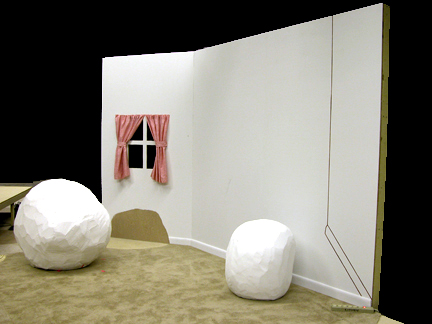

Installation, ROOM.

FK: For me, the scale and context (performance as opposed to gallery setting) has raised so many new technical (and conceptual) concerns about how to safely support the weight of 60 or 70 people; how to accommodate to their bodies, their fields of perception, and their movement. We have made many decisions about how the principal concerns of ROOM can permeate the structure as well as the video and the performance. For instance, we thought a lot about where one element ends and another begins, how they can be reflected, mirrored and repeated in different places and in varied ways, where and how those designated parameters redefine a space or a form a narrative, how they overlap and interact with one another to challenge the properties of video, sculpture, and sound. For instance, we cut a hole for a pond area exposing the understructure of the stage. Wynne placed her chroma key green paper in the pond, exposing the structural element of her video process as well. These kinds of discoveries happened a lot for us throughout our process, and we have remained very open to them as well.

LT: One thing that really strikes me about this project is how necessary and relevant the model of the feminist consciousness-raising group is in light of the current reactionary political and social climate in America. It feels so much like we've backtracked straight into the 50s. How do you think we can use the space you've created to return to some of the issues that were raised, but not necessarily fully addressed, by early feminists? What new insights and positions can we bring to the table?

FK: Reaction is always dependent upon an external force. Creating the space to look inward is where we can speak with a voice that's clear and vulnerable, not out of fear and opposition but out of strength and knowing. We've created a space to initiate a new social architecture--and I mean architecture in the abstract sense as well as the literal. We need a new structure to engage and support one another, because the modes that are being used, you're right, are not suitable to the demands we have anymore. I believe ROOM can function as a reminder to and inspiration for the power of movement.

WG: And the power of imagining and re-imagining. Well really what does it mean that we KEEP going back? Zigzagging through our own present and recent past. One good thing about it is that, as feminists, we are starting to have a catalogue of sorts, a library of ideas and models and questions. As those ideas get eaten up by the mainstream and media cultures, we need to not just slip on the shit they leave all over the place but use it for planting more of our gardens. Oh my god that was a wild metaphor, but it is necessary to return to the old garden plots and look at what was once growing there. It's like you have your grandmother's name but you are your own carol or anne or cleo. But still you have your grandmother's name. So you have to wonder what she was like.

But ROOM isn't just a cool re-imagining of the 70s style. This is an actual need that I feel in my community, and every day at the grocery store or on the subway train, for dialogue. For presence in our lives and our intimacy with our worlds. By again addressing ideas of performance in our homes and in our intimate lives, as well as process and communication, but now with a history of doing just that, we make it a practice, a discipline. Where is our physicalness? In our tv culture, in our computer culture, where is our physicalness? It's almost startling to hear our own voices. Let alone someone else's in a quiet room talking with no pretension, no jokes, no performance, about how they are living.

LT: In another interview published on this website ( WORKING #4 ), Ulrike Müller raises a question about the politics of self, and feelings as political states. In light of the fear, anxiety and depressive moods provoked by the current status quo, she asks if and how our emotions can "be shared and made productive in a practice of consciousness raising which does not solidify into identities?" I find her question really germane to this discussion of collaboration and collectivity. Is it possible to use categories such as "radical feminism"; and "queer politics"--which imply certain notions of collective identity--as tools towards a type of non-prescriptive consciousness raising that is simultaneously idiosyncratic and collective?

WG: The biggest thing I've learned from this collaboration with Fawn is trust. I don't have to have Fawn's identity, I just have to trust hers and trust her with mine. That said, it has been really interesting to construct a totally radically political space with someone who does not share my identity or the political language that I've learned with it. What does that mean? What does that mean, I ask, as I'm sitting in this feminist room, this feminist performance space and work space? Well it means it got built. But it also means, for me, that it is smarter because it grew up learning like five languages instead of one. Languages of healing, of teaching and learning, of lesbian politics, of communication, of trust. There's actually a lot more, but I'll stop there. Fawn and I have spent hours and days and weeks now talking together, intimately, about our lives and our work, our needs, our desires. And at the end of it I too have learned new languages, and new words in my own. My identity feels stronger, my community feels bigger.

Performance video still of Tracy + the Plastics band member Nikki,

ROOM performance.

FK: Raising consciousness is first a process of individuation, autonomy, self-reflection. Then it is a space of unity, collectivity, and community. When we practice consciousness, we are cultivating ourselves as well as setting a model for others. I feel consciousness can only be raised with the gesture of acceptance and inclusion. This gesture is the radical act for me because it means remaining open regardless of the risk.

LT: For those of us who have a nostalgic memory of the sort of American middle class carpeted library/living room architecture evoked by the space, ROOM feels very comfortable, familiar and safe. Can you talk a little bit about your desire to create a "safe" space for dialogue and how this shaped your decisions about the form of the installation?

FK: That sense of safeness comes from the intention invested in the material, the labor, the conceptualization of ROOM. Intention takes up no space, but I believe it is integral to defining and transforming it. The intention was to invite others to participate in a voice of self-ownership, of community, cooperation, participation, and action. When we feel safe, we can begin to consider alternative possibilities and resolutions, we can learn to truly express ourselves, and we can be available to really understand one another. Feeling safe subdues our reactionary impulses, as you brought up earlier, and offers a more reliable, fertile ground for building and standing on.

WG: I move around in a lesbian body 24/7 and so I absolutely create safe spaces in my home, in my art, driving through Wyoming, Ohio, or New York. Especially in a culture that has invested a disapproval, hatred, and also a "sanding down" of that body. But you know, also as a performer I wanted a safe space. I’ve come to know the stage as a home. A place for me to live. At the performances we're not serving alcohol, people are invited to take off their shoes. I'm asking the audience to be as present as I am. To be safe with me in the space.

LT: What were some of your discussions you had in developing the unorthodox seating arrangement and integration of the performance space with the audience space?

FK: Wynne and I have had many discussions about non-hierarchical sounds, video, form... Where structural elements don't peak or become erect or vertical; they're not linear. This is linked to building an architecture for the female. What does this mean? How can we build if we don't build up? In thinking about the seating, I considered the role of choice as a kind of stance--where someone stands--the act of sitting or standing as a kind of possibility for empowerment. There are three main seating elements loosely corresponding to the idea of a triad or triplets. Each seating structure offers a different way for the body to relate to it- one more in a reclining fashion, one in a seated fashion, and in a standing fashion. It will be interesting to see how others choose to fill the space- where they enter the stage- as there is no distinct or formal entrance, and where and how they choose to sit in it. People will also be invited to seat themselves on the floor of the stage. We both wanted everyone to be on the stage, to share the stage with Tracy + the Plastics.

I am inspired by the idea that ROOM as a sculpture is not complete without its audience, that the audience creates the volume of its own form. And that form is the product of connection and engagement, not autonomous or externalized from the viewer.

WG: We also talked so much about creating a home and a landscape.

LT: For Room, not only did you two work collaboratively, your individual groups of friends, who might not otherwise have known each other, have met as participants. What has that been like?

Performance video still of Fawn Krieger, ROOM installation.

WG: It really has been incredible to welcome and feel welcomed by new friends and peers. We built a community as we built the room. Our ideas felt held up by these other hands, holding a corner while we balanced the main weight. Fawn has such an awesome way of making everyone in a room feel comfortable and connected. I learned a lot just about introducing people to each other. She always immediately makes sure everyone is told everyone else's names. I think she carries a home-ness with her that is so evident in the people she has in her life. And I've been so moved by my friends that have been a part of it too. It means so much to have another person connect with you in your art. Intimacy and trust.

FK: It's interesting, you know, that there's so much trust involved with collaborating with another artist, not only in the project itself, but who else gets brought into it. It has been so amazing to meet Wynne's friends, to see how much they love and support her and her work. Their willingness to accept and help me as well has felt so inclusive and warm. And I believe this has been likewise for Wynne. I feel like I've learned so much about her community, and I'm just so moved by the love that surrounds her, it's really informed ROOM in so many ways, it's helped to build it, and to fill it. I hope others feel surrounded by this sensation when they enter the space.

I have come to feel like collaboration is really the core material of this project, not wood or carpet, or perhaps even video. It's the communication that helped our minds make space and allowed our bodies and our hearts to fill it.

LT: When I first heard about Room, I was reminded of the 1972 Womanhouse project, where a group of feminist women artists (including Miriam Schapiro, Judy Chicago and Faith Wilding) collectively refurbished a house so that each room contained installations addressing issues of the construction and experience of female identity. The project also included consciousness-raising sessions and live performances. Was the Womanhouse a historical precedent for you when you were creating ROOM? Were there other historical projects, protests, structures or performances that inspired you?

WG: I actually did not know about womanhouse until this fall when Christina Yang (of The Kitchen) told me about it and suggested looking to it for inspiration and history regarding ROOM. And she just gave me a copy of Judy Chicago's book "through the flower," which I've been reading feverishly on the subways.

I was making a video for Le Tigre this summer and I was looking for old women's movement protest footage. I realized how little I knew about the every day happenings of that movement. I can name the biggest books, the most outstanding women, the problems, the theories, but what happened every day?

So I was thinking about that. And K8 Hardy’s performance "beautiful radiating energy" really inspired this urgency in me this summer.

FK: My process involves working from the inside out. In locating a voice, an origin, a personal history, I find the core content of my work. My concern is centered around what it means to feel home, to build a home, to occupy a home, to be protected by a home. How can we carry home with us so we feel safe when we might otherwise feel threatened? How can we build homes that relate to our personal needs, and what are we building on top of to do this?

Wynne brought up the consciousness raising group idea, and it fit so seamlessly with my interest in becoming conscious through the act of designating, building, and inhabiting a home.

Performance video still of Lanka Tattersall, ROOM performance.

LT: Fawn, can you talk a little bit about some of the non-patriarchal architecture that you’ve been looking at for this project?

FK: For this project, I have been thinking a lot about animal architecture, where nature of the environment meets the nature of an animal. In thinking about a space for the female, I thought of beaver dams, a home built to house a family and social activity. Containing both air pockets and water, beaver dams look like a mound of mangled twigs and branches from above. The word "Beaver" has been used as a derogatory term for women. My interest is in repossessing and redefining this word, learning from this animal's social and physical intelligence to build and protect, shelter and nurture, has felt so transformative for me.

I';ve also been thinking about beehives and honeycombs. I've been reading extensively about Shaker design and their early belief system in equality for the sexes--this is from a community that witnessed the original conception of the United States of America--a religion born parallel to mass colonialism in this country. Their utopian belief structure was so innately manifested in the forms they made, which to me, as a sculptor, is such an inspiring model. Native American architecture is fascinating to me, and also, I've been looking at a lot of American suburban interior design images from the 50s onward. Those rigid bedcovers and basement conversions are endlessly fascinating.

LT: How does the Room installation respond to the notion of gendered architecture? Are there things in the installation that shape it as a space for lesbian bodies? Feminist bodies?

FK: My idea of male and female is not of form, it's of energy, of vibration. I don't believe presence is determined by the physical occupation of space, but by the spiritual frequency that inhabits it.

I don't see my concern for a current and active female vision and voice to be affiliated with my orientation. I believe women can't afford to be unconscious of the powers they align themselves with, and I don't believe men should afford this either. For me, the lack of space for the "Feminist body" or the "Lesbian body" is a more concise way of breaking down a cultural lack of space for the woman's body in general--the real woman's body--a body of strength, solidness, choice, love and compassion. ROOM makes space in its construction of material form, in its presence, as opposed to its absence of matter. ROOM is intended to be aggressive, not in its forcefulness, but in it's embrace.

WG: I was just talking about the body shapes that are placed around the room, trying to explain why they are there or what they mean to me. And I began talking about how as a lesbian woman and a feminist, I'm required to project my body onto that of the mainstream images of women. Even for hair care products, it is hairspray for straight hair, not lesbian hair. So I have to be able to imagine that the woman in the ad is a lesbian in order to want to buy the product. I have to be able to abstract my body, and hers. To look at the tree and see a bush. Anyways, the body shapes offer a chance for people to do just that. To imagine new bodies there, to imagine safe bodies, exciting bodies, or forgotten bodies. Also they feel like the memory-bodies of women who once were in a consciousness-raising group.

LT: How do you define collaboration?

FK: Honesty, trust, communication, openness, loyalty, respect, inspiration, generosity, inclusion, integration, faith, dependability, intimacy, fun, and of course, giving one another room.

LANKA TATTERSALL is an independent curator living in New York where she is finishing her Master's degree in Modern Art and Curatorial Studies at Columbia University. She is a co-editor of the queer feminist collaborative journal LTTR and the current Curatorial Fellow at The Kitchen.

© Lanka Tattersall, Wynne Greenwood, Fawn Krieger, 2005